Jan

Week 46: Nutcracker Buck sings “The Last Buffalo”

by Nutcracker Buck in Uncategorized

I made two C’s in my academic career. The first one was the second semester of my freshman year in a class called “Astronomy in Science Fiction,” taught by Ethan Vishniac. I remember very few of my undergraduate professors’ names, but I remember Professor Vishniac’s, because it sounded like a character in a science fiction novel [Note: Just looked him up on Wikipedia. Man, he came from an estimable family.] I don’t remember anything about the class except that I was lost and terrified throughout. What possessed me to take a class combining two subjects one of which was over my head [sic] (I’d made a B in Astronomy and hadn’t deserved that) and the other of which I’d always hated, I do not know.

My dislike of science fiction generally and space fiction particularly is matched only by my dislike of submarine fiction, and the dislikes arise from the same visceral distrust of genres where there are no rules. In both submarine and space stories, you never know where north is. The people just scurry around, in space, underwater, or in the spaceship or submarine itself, and you never know where they’re going or why they are where they particularly are. “Look, another submarine room full of pipes and stuff! Look, another planet or asteroid or something with some made-up name! I wonder if they’ll get away from the bad guy! Yes, another submarine room, another planet!” That stuff gets boring. There’s no suspense because the author can always just invent another room in the submarine or head off to another part of the limitless ocean.

I hate hobbit stuff, too, where it doesn’t matter if somebody dies because, hey, here’s some magic!, and he’s alive again.

I made a C in Vishniac’s class and was glad to get it. I transferred from UT immediately. Then a bunch of other stuff happened and . . . hey, here’s some magic!, two schools and a semester-off later I wound up graduating from UT with no loss of credits and in four and a half years, as though I’d never left.

A couple of years later, after a year in St. Louis I’m no longer sure happened at all, since there are no witnesses to attest to my presence there, I wound up back at UT for grad school in English.

The degree requirements allowed you to take some classes outside of English and even one or two undergraduate classes. My friend Ailise, an American Studies grad student with a yen for cowboy kitsch, talked me into taking an undergraduate class about the American West.

It wasn’t the stupidest class I’ve ever taken—the stupidest one I ever took was (redundancy alert) “Law and Fiction,” and I still have dreams about missing the final for that one—but it was pretty bad. The professor had one thesis, which he reiterated about a thousand times an hour. The thesis went something like this: “Hey, you know those cowboy movies? It wasn’t really like that.” So we’d watch a movie and he’d tell us why “it wasn’t really like that.” He’d tell us something he thought we thought and tell us we were wrong, because it wasn’t really like that. (For instance, most singing cowboys on the open range didn’t have invisible orchestras following them around. “It wasn’t really like that.”) Vishniac’s class had the same sort of thesis: Time travel isn’t really possible![1] And a few years later in Arkansas I met Kevin Phelan who told me about his high school physics teacher who was obsessed with impressing upon his students that everything has torque. That class, according to Kevin, consisted of the teacher referencing some object and pointing out that it had torque. “That desk has torque. Your clothes, torque in them. There’s torque in stoves. Marbles? Full of torque. All kids’ games have torque. . . .” The final exam was a single question: “Name some things with torque.”

I made a C in the American West class. I made A’s in every graduate level class I took (except that one of my fiction workshop teachers gave me a B, which I’m kind of proud of, because nobody gets a B in a graduate fiction writing workshop). But I made a C in an undergraduate class about stuff that happened in my own backyard.

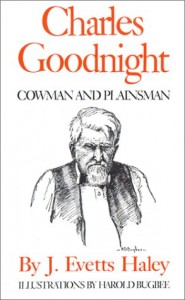

Charles Goodnight. Charles Goodnight is the more famous member of the partnership he had with Oliver Loving. Frank Dobie said Goodnight “more nearly approached greatness than any other cowman in history.” (Think about that next time you’re discouraged in your quest to become the greatest Mexican hockey player.) But Goodnight had the advantage of outliving his partner by 62 years; Loving died of gangrene from an infected arrow wound in 1867, while Goodnight lived to the age of 93, dying in the Panhandle in 1929.

Charles Goodnight. Charles Goodnight is the more famous member of the partnership he had with Oliver Loving. Frank Dobie said Goodnight “more nearly approached greatness than any other cowman in history.” (Think about that next time you’re discouraged in your quest to become the greatest Mexican hockey player.) But Goodnight had the advantage of outliving his partner by 62 years; Loving died of gangrene from an infected arrow wound in 1867, while Goodnight lived to the age of 93, dying in the Panhandle in 1929.

My dad sent me the J. Evetts Haley biography of Goodnight last week, which is what inspired me to write this song, though I haven’t started reading the book yet. Coincidentally, Saturday afternoon I turned on the TV to distract the kids from the apparent ceaseless misery and horror of their lives and tuned into one of the PBS minor league stations we now get since we moved up to the HDTV. On offer was an episode of Ray Miller’s eighties program (redundancy alert) Texas: Our Texas, a study in cowboy polyester that deserves its own write-up, and the subject was Goodnight and Loving. It was the first time I’ve ever heard the trail referred to as the “Goodnight-Loving” Trail as opposed to the other way around. So Goodnight’s longevity and the fame proportional thereto are still paying dividends.

I grew up in a little town named after Loving, or at least after one of his descendants. Loving died in New Mexico but was buried, thanks to his friend Goodnight, in Weatherford in Parker County (the lead characters and many of the events in Lonesome Dove were based on or at least inspired by Goodnight and Loving and their exploits. You probably already knew that.) Parker County is a couple of counties east of Young County, but some of Oliver Loving’s clan made their way to Young County before the end of the 19th century. I rode the schoolbus with Loving’s great-great granddaughter (or close enough), Laura Loving, a name so pretty it sounds made up.

All of that is to say that I don’t have any deep affinity with or connection to Goodnight (or Loving, beyond his name on my hometown) and don’t know why Dobie would have thought the man came nearer to greatness than any other cowman. Maybe I’ll know when I read the book. They weren’t household names the way Stephen F. Austin and Sam Houston were. Goodnight’s and Loving’s pioneering of the cattle-drive was impressive—what fool would have thought you could make a herd of cattle travel a couple of thousand miles through all sorts of irritating weather to be slaughtered?—but I don’t know that the cattle-drives had any long-lasting influence on the development of the country other than help create the myth of the cowboy (which is something, of course, but I don’t think that was what Goodnight and Loving were aiming to do; they just wanted to make money.) If he hadn’t driven those cattle to Chicago, people would have just eaten something else. The cattle-drive era was only about twenty years; pretty soon the railroads made the cattle-drive obsolete, and I don’t think there was any connection between the cattle-drive and the opening up of new markets—the railroad was coming anyway.

Goodnight today would be (and probably is) regarded as a robber baron, imperialist and genocidal maniac, but of course if he were alive today he wouldn’t be doing those things, or at least he’d do them in a different genre, in a way that would be celebrated today and derided by the pod people of the future. I don’t know who he’d be—probably a real estate developer. (I’d probably be trying to get his legal work.) He has to be judged by the standards of the time he lived in, and I wasn’t there. He invented the chuckwagon. He might have a claim to paving the way for America’s lasting contribution to world cuisine, which is taking other people’s cuisines and putting them on a stick.[2]

The Last Buffalo. The song is based on a purportedly true but unverifiable Goodnight story. The story is that a group of Indians came down from a reservation in Oklahoma asking for a buffalo from Goodnight’s personal herd. This was long after the Indian wars were over. He gave them one, thinking they would take it back to the reservation. Instead they chased and killed it with lances there onsite. It’s a powerful story that can be interpreted in a lot of ways, most of them arising from “imperialist nostalgia” (in Professor Alex Hunt’s memorable phrase.)

I heard the story first and second from John Graves. In Goodbye to a River, Graves recounts the story factually, or at least surmisingly. Later he wrote a short story based on it, called “The Last Running.”

I’ve relied heavily on the Graves elaboration on the story (that’s nothing; I’ve relied on John Graves for big chunks of my life), which I try to acknowledge in the title and with the character’s names (he has Tom Bird and Iron Shirt; I have Tom Preston, which is my son’s and grandpa’s name, and Iron Bird). It was Graves who removed Goodnight as a character but retained him as an offstage presence (as the donor of the buffalo) and who also invented the past relationship between the cattleman and the Indian foe. I took all that and added a grandson and a blizzard.

As for the quality of the song, well, if this is the sort of song you like, you’ll like this song. I am somewhat saddened that I didn’t make it all the way through this project without doing a song in a minor key. I have a prejudice against minor keys because most of the time it’s a cheat. “You can tell I’m sad and serious because I’m singing in a minor key.” But if you’re going to do one of those new-agey Native American mysticism type of songs, it needs to be in a minor key, preferably with a rain stick and some spooky flutes.

Only a couple of songs in this project have been heard by anybody else before being posted here, and this is one of them. I had it on CD when I took Thomas to Tae Kwan Do on Thursday, seeing how it sounded on car speakers, and was pleased that he sat transfixed through the whole thing. At the end I asked him if he liked it. I thought maybe he’d comment on his name being in the song. It took him a minute to say anything, and then all he said was, “Why was his blanket moldy?”

That’s How I Got To Fayetteville. Sorry, I lied last week. This song came up suddenly, and then I spent too long getting that scroll thing to work on the video and didn’t have time to shift gears to the Fayetteville piece. It wouldn’t have fit here anyway. I’m getting concerned that I won’t cover several things I’ve been advertising for a long time. I’m also just about ready to concede at least three letters of the alphabet. I have an O and K song but will likely not use the K. I don’t have an X or U song. I do hope to write the Fayetteville piece and to continue working out the Tom T. Hall Relativity Principle, which is still evolving nicely. We now know, for instance, that Tom T. Hall has torque.

[1] Bullshit.

[2] Steve Runner’s joke.