Posts Tagged ‘nutcracker buck sessions’

Dec

Week 40: Nutcracker Buck Sings “Smells Like Something Died in Here (and I Think it’s Our Love)”

by Nutcracker Buck in Uncategorized

I could see this one being covered by Brooks and Dung.

This is not one of the new breed of “songs with commercial intent” heralded in the last post. This one’s just a regular dumb nutcracker song I’ve had hanging around awhile, one of the several I’ve had stacked up on my “bridge repair needed” shelf. Songs like this one need bridges if their existences are to be justified, and every bridge I try to write winds up sounding like either the bridge from “Jesse’s Girl” or the one from “Two Tickets to Paradise.” Those songs typify “bridge” to me, for some reason. I may have already said that. I probably started repeating myself in Week 2 and just don’t remember it. Anyway, this bridge is no great shakes and doesn’t really make that much sense—it’s obvious that it’s just there for the rhyme—but I’m tired of the song being on the shelf. We’re on the home-stretch; it’s time to start clearing the shelves.

Video. That’s Eleanor with the painted face. Eleanor and Rona are buddies. They put on the Jingle Cats CD (Christmas songs meowed by cats) and dance to it for hours here at the house. That’s almost as bad as the Renaissance Faire. “We Three Kings of Orient Are” performed by cats is particularly excruciating.

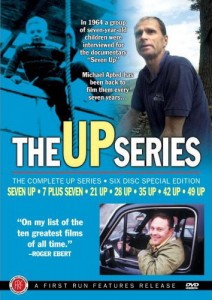

Up Series. Today’s the day I’ve set aside to push for finishing the opera, so no tome-length essay today. I’ll start clearing a few shelves in that regard, too—stuff I’ve been meaning to mention and/or link for, in some cases, several weeks, but have had no segue to get to. I’ll start with the Up Series.

Up Series. Today’s the day I’ve set aside to push for finishing the opera, so no tome-length essay today. I’ll start clearing a few shelves in that regard, too—stuff I’ve been meaning to mention and/or link for, in some cases, several weeks, but have had no segue to get to. I’ll start with the Up Series.

Here’s what it is: in 1964, a British television production company made a half-hour film about fourteen seven-year-old British schoolchildren, called Seven Up, with the plan of revisiting those same children every seven years to chart how their lives had changed. The notion was based on the Jesuit maxim that if you “Give me the child until he is seven and I will show you the man,” or something like that. The first film was directed by Paul Almond; every subsequent one has been made by Michael Apted (director, strangely enough, of one of my favorite movies, Coal Miner’s Daughter.) Janet and I have been watching them over the last couple of months—we’ve seen all but the most recent one, 49 Up—and they are, very quietly, spell-binding.

I’ve been holding off on talking about the series because I’m trying to formulate some thoughts about what makes the series so . . . noble (to use Roger Ebert’s characterization of the works.) I’ve been wanting to use the series as a springboard to advance my argument that one of the things that comes with growing older is a deeper appreciation of process over product, which is one of the things I think I am learning from doing this project. Back when I was trying to write books, I would hear talk of how impressive it was just to finish a book. I never bought that, and I doubted the people who offered that conciliatory note bought it either. The point wasn’t to finish it; the point was to make it good, to publish it, to gain riches and recognition, etc.

Now, though, I’m less impressed by the particular product anybody produces, usually, than I am admiring of the effort and the belief that goes into the making of it. I’ve read plenty of books and listened to plenty of songs. It’s unlikely that there will be that many that come along that really, in and of themselves, change my world view the way a book or song or movie or even a football game could change my worldview when I was in my teens and twenties. So what is so admirable and noble about the Up Series is that somebody envisioned it and dedicated himself to seeing it through. It’s unlikely that there are going to be any huge secrets of life revealed in that last episode, if there is a last episode or if it’s known at the time that it’s made that it is the last episode. What will exist is the series and the lives, then ended, that went into the making of it.

The series itself follows those fourteen children into their 14th, 21st, 28th, 35th, 42nd and 49th years; 56 Up is due out in 2012. (The subsequent installments are more in the two-hour range, sometimes longer.) The series was born out of a naturalistic and pessimistic world view; its original premise was that class determines all. The children were selected from a variety of upper-class and working class backgrounds on the theory that there would be little improvement in the lots of the working class kids (the ones from Liverpool, from London’s East End, and the two kids plucked from an orphanage) and that the upper class kids would retain the world by the balls.

That view is only partly borne out. All of the children are asked at seven what they think they will wind up doing. The three poshest of the upper class boys predict that they will attend a certain boarding school, matriculate to Oxford, and go into careers in law. With a minor variation on the part of one of the boys (who didn’t get into Oxford and wound up in journalism), that’s what happened. But the scrappiest of the lower class boys, Tony, worked as a jockey and stablehand, learned “the Knowledge” (the famously difficult test London cabdrivers have to pass to demonstrate an intimate familiarity with the streets of the city), takes small acting roles, and wound up owning three houses on a cabdriver’s earnings, including a holiday house in Spain. One of the most promising boys is living in a squat at 21, is homeless at 28, and at 35 has migrated to the ends of the earth, the Shetland Islands far off the north coast of Scotland, clearly losing his mind. A farm boy who at 14 had been no further than Manchester, and there only once, winds up a nuclear physicist at the University of Wisconsin. All but one of the women (there are only four; Apted admits that the series got off to a bad start by not balancing the gender scales) go through divorces and wind up single mothers.

Although series takes on a more personal than political tone as it progresses, Apted, who is the interviewer as well as the director, occasionally tries to press the participants back into the mold that was envisioned at the beginning of the series; he seeks to make the participants from working class backgrounds confess how miserable their lives are. He gets striking pushback, especially from Jackie in 42 Up, who essentially accuses Apted of showing up every seven years for a couple of days and presenting his findings as her life. That is not my life, she tells him. I am not unhappy, Michael! she tells him. She is 42 years old, divorced with three young boys to raise, living in dreary public housing in Scotland, confronting various serious health issues, being invaded every seven years by British television, but she refuses to let any of that or Apted define her happiness. And Apted very decently lets her get the last word on that.