Posts Tagged ‘wallace stevens’

Sep

Week 29: Nutcracker Buck Sings “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”

by Nutcracker Buck in Uncategorized

“NO ‘WISH YOU WERE HERE’!”

—Sign in the acoustic guitar room of Rockin’ Robin Music Store in Houston

Wait a minute. Is that . . . prog rock? I think it is! It’s prog rock!

I don’t care what you say. I like it and I’m keeping it. It was free. I was messing around with the recorder on Wednesday, in my eternal quest to get the levels set right for recording an acoustic guitar (Are they just not meant to be recorded? Has nobody else ever had this problem?), and started playing what you hear on this song (not quite, but more on that below). It wasn’t a chord progression I’d ever messed with before; it just kind of happened. I’d been trying to record a song about Legos but couldn’t get the guitar right. I started playing this progression because I was sick of the Legos song.

I didn’t think much of what I was playing until I listened to it played back, and I thought it sounded pretty good. I turned the recorder on again and played it through a few times, singing nonsense lyrics, to see if there was a melody there. There wasn’t, but it had something anyway. I put a bass-line over it. I threw on an electric guitar with lots of delay and sustain. Still I wasn’t entirely invested in it, but by this point I thought, “Hey, that sounds pretty good. Wish it was a song.”

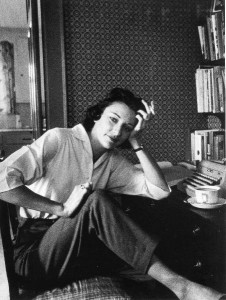

I had good enough sense to know I’d never come up with any lyrics for anything that sounded like that. I wondered what would work. I thought of Anne Sexton’s poem, “Her Kind,” which is a spooky poem by my favorite crazy female suicide poet.  I’d always heard that poem as a modal/minor-key song. But it didn’t really fit the meter of these chords. I went in the house and started looking through various poetry books and anthologies. I was thinking Yeats or maybe John Berryman (my favorite crazy male suicide poet), maybe that John Berryman “Dream Song” that goes, “I’m scared a lonely, never see my son . . . .” Nope. Nope. I have Wallace Stevens’s Collected Poems but didn’t really think of him as being a candidate for this song. He writes bagpipe and flugelhorn poetry. I.e., his poetry never struck me as being terribly musical.

I’d always heard that poem as a modal/minor-key song. But it didn’t really fit the meter of these chords. I went in the house and started looking through various poetry books and anthologies. I was thinking Yeats or maybe John Berryman (my favorite crazy male suicide poet), maybe that John Berryman “Dream Song” that goes, “I’m scared a lonely, never see my son . . . .” Nope. Nope. I have Wallace Stevens’s Collected Poems but didn’t really think of him as being a candidate for this song. He writes bagpipe and flugelhorn poetry. I.e., his poetry never struck me as being terribly musical.

But I’ll be danged if “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” didn’t just jump right into those chords like it belonged there, if I do say so myself. As a bonus, the poem, published in 1917, is in the public domain! (Copyright law is complicated, but one thing that is black letter law is that if it is a written work published before 1923, it’s in the public domain.)

And of course when I tried the poem over the chords I found that I hadn’t recorded enough measures to make all the way through the poem. There was only enough for eight of the ways of looking at the blackbird. For two days I debated just going with it and calling the song “Eight of Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” but on Friday I did do the whole thing over, same levels, same effects, everything. And it sounded like . . . this. Whereas the eight-ways version sounded great. Or so my imagination tells me. Anyhow, here’s all thirteen ways and six and a half minutes of looking at Wallace Stevens’s blackbird. The original poem is here.

Wallace Stevens and Others. I’m glad the Stevens poem worked out for this song, because I’ve always felt guilty for not liking him more. I’m scared of Wallace Stevens. He’s one of the giants of 20th century American poetry. As a guy shooting off his mouth on the internet with no peer review and no accountability controls and no consequences to suffer for misstated facts and misguided opinions, I’d say the biggest of the big guns in 20th century American poetry are Wallace Stevens and William Carlos Williams, flanked by Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell and Marianne Moore.

Lowell’s stock fluctuates pretty wildly, but he’s still to credit (or blame) for the confessional school of poetry that reigned for so many decades and may still reign; I don’t really have a finger on the pulse of the poetry scene any more. I don’t say that facetiously; I used to keep up with that sort of thing inasmuch as it’s possible and inasmuch as any non-poet tries to keep up with it. Others might put Hart Crane in there, or any number of other poets. Williams’s “Red Wheelbarrow” and Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” are the two biggest “WTF?” poems in an American high school kid’s life. Remind me to do a long-winded opinion piece on why we shouldn’t “teach” poetry.

I don’t include Eliot or Auden (who, along with Yeats, are my three favorite poets) because the category is 20th century American poetry, and in both a political and an aesthetic sense neither Eliot nor Auden, both giants on the world literary stage, qualify. Eliot was born in St. Louis but became a British citizen and pretty much an Englishman and an English poet. Auden was English but lived much of his life and wrote much of his poetry here. Anybody who read both poets and didn’t know anything about either of them and was asked to guess which was American and which was British would probably guess Eliot was the Brit and Auden the American.

Yeats was Irish. Boy, was he Irish.

Auden’s my favorite of them all. I have his Collected Poems as well, and it’s usually out of the bookcase lying around somewhere. I didn’t consider any of his poems for the song (well, briefly, the fifth of the “Five Songs,” also sometimes titled “Nocturne,” which is the second poem quoted in this article from the New York Review of Each Other’s Books) because I think he’d mildly, avuncularly disapprove. His poems are very calm, wise, measured and beautiful. He wrote both of my two favorite poems: “Atlantis” (to which the tagline of the nutcracker website nods) and “The Shield of Achilles.” He doesn’t go all crazy in any of his stuff. He lets Yeats do that instead. Auden is not passionless, but he isn’t going to invest too heavily in any earthly emotional matters. You drink and mourn and shake your fist at the heavens with Yeats; the next day you go confess to Auden, because he’s heard it all before.

Eliot wouldn’t be on my list except for the Four Quartets, which I memorized when I was in my mid-twenties (I think I’ve mentioned that way back in the beginning of this blog somewhere.) That’s not terribly impressive, I think, but it’s pretty odd. I was on a big memorization kick back then. I just went around memorizing stuff. That poem, actually four long poems broken into five movements (so I’m not sure why each is called a “quartet”), is a structured meditation on everything but the kitchen sink. Eliot’s stated goal was to achieve the artistic purity of music using only words. I tried that too. It’s tough. I wound up getting a guitar.

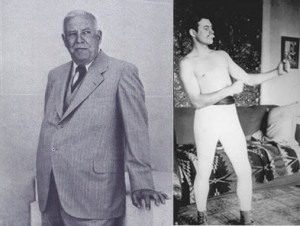

Stevens, though, is hard to love. Hard for me anyway. So many of his poems, most of them, in fact, just seem to kind of stare at you. It’s like you’re in a cartoon in which you hear a party going on, but the second you open the door the music stops and the lights go out. You stand there perplexed, close the door gently, and the party starts up again. Other than about a half-dozen of his poems (i.e., the anthologized ones), I can’t make head nor tail of anything he wrote. “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” is one of the canonical ones and one I like very much. It sounds and looks like the opening frames of a horror movie. Stevens has a compelling and unusual biography for a world class American poet, or any poet for that matter. He didn’t start publishing until mid-life and didn’t get major recognition until he was in his fifties. The guy was a lawyer and insurance company executive. He worked for Hartford Insurance Company in Connecticut, the one with that deer logo. In the summer he’d go down to Key West, this buttoned-up East Coast insurance executive who wrote the freakiest poetry of the first half of the twentieth century, and get in fist fights with Ernest Hemingway and Robert Frost. Poets used to be a lot more interesting. Or maybe insurance company executives did.

Blackbird Graphic. The poem apparently is a favorite of graphic designers. In searching for images to use for the video, I found lots of really interesting graphics work done based on the poem. I went with Maureen Shauhnessy’s spare rendering of a blackbird in bare limbs. She can be found at ravengrrl.blogspot.com (but I found her picture on flickr.) I don’t know her and haven’t figured out how to contact her but thank her here.